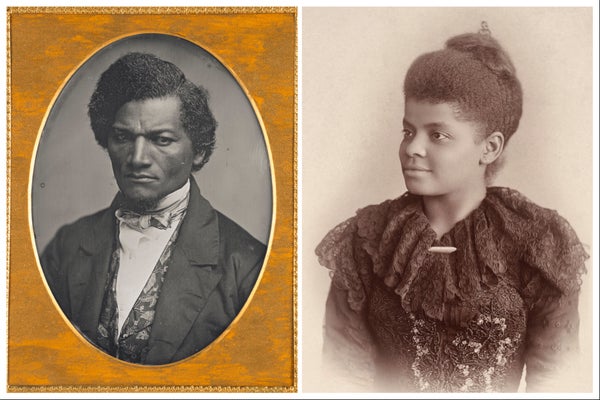

In the 19th century, the most photographed man in the world wasn’t Walt Whitman or Ulysses S. Grant or even Abraham Lincoln. It was Frederick Douglass. The famous orator and abolitionist was known for using his eloquent voice to impart the horrors of slavery, which he had experienced firsthand. He traveled all over the country, speaking to large crowds and making arguments to end the enslavement of Black people. On the days when there were no scheduled lectures, he would visit a daguerreotype studio to have his picture taken. He enlisted these images as another thrust of his campaign, offering the public a positive view of a Black person to oppose the negative caricatures that were commonplace in newspapers. His handsome portrait was a weapon against these malicious images, because his photographs were sold by, and distributed from, the studios he visited. With them, picture by picture, he slowly changed the public’s perception of an African-American. Frederick Douglass knew back in the 19th century that Black images mattered. 在19世紀,世界上被拍攝次數最多的人不是沃爾特·惠特曼、尤利西斯·S·格蘭特,甚至不是亞伯拉罕·林肯。而是弗雷德里克·道格拉斯。這位著名的演說家和廢奴主義者以其雄辯的口才來傳達他親身經歷過的奴隸制的恐怖而聞名。 他走遍全國,向大批人群發表演講,並提出結束對黑人奴役的論點。在沒有預定講座的日子裡,他會拜訪銀版照相館拍攝照片。他利用這些影像作為他運動的又一次推動,向公眾展示黑人的正面形象,以對抗報紙上常見的負面漫畫形象。他英俊的肖像成為了對抗這些惡意形象的武器,因為他的照片是由他訪問的照相館出售和分發的。憑藉這些照片,一張又一張,他慢慢地改變了公眾對非裔美國人的看法。弗雷德里克·道格拉斯在19世紀就知道,相片中的黑人形象至關重要。

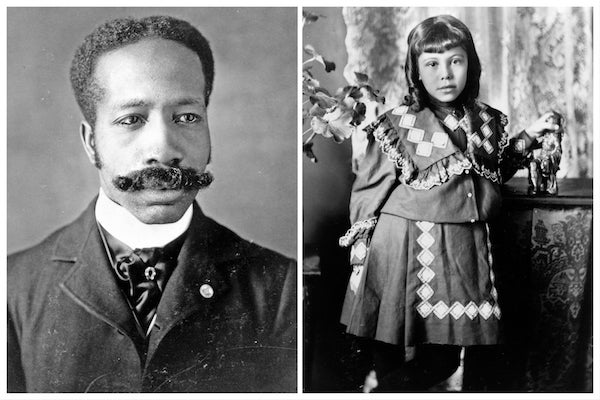

When Douglass had his pictures taken, rendering an image of a person was a democratic expression. For a small sum, the kitchen chemistry to sensitize a glass plate made it easy for anyone to have his or her image captured. Doing so became even easier as photography was adopted as anAmerican pastime, and camera manufacturers not only produced film, but processed it. Taking pictures became a big business. And W.E.B. DuBois, an African-American scholar born about 50 years after Douglass, also had great hopes that it would serve the cause of racial justice. DuBois knew the power of displaying Black images to sway the American consciousness. And he used pictures to showcase his race’s achievements with material that included portraits of educated Black individuals, images he showed in his Exhibit of American Negroes at the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris. 當道格拉斯拍攝照片時,為一個人渲染影像是一種民主的表達。只需少量資金,對玻璃板進行感光處理的簡易化學方法使任何人都可以輕鬆捕捉自己的影像。隨著攝影被採納為美國人的消遣方式,這樣做變得更加容易,相機制造商不僅生產膠捲,還衝洗膠捲。拍照成了一門大生意。W.E.B. 杜波依斯,一位在道格拉斯出生約50年後出生的非裔美國學者,也對攝影寄予厚望,希望它能為種族正義事業服務。杜波依斯深知展示黑人形象以影響美國意識的力量。他利用照片展示他種族的成就,其材料包括受過教育的黑人的肖像,這些影像他在1900年巴黎世界博覽會上的“美國黑人展覽”中展出。

African-American man (left). African-American girl standing next to table (right). Both images are from Types of American Negroes, compiled and prepared by W.E.B. DuBois. Credit: Getty Images (man); Getty Images (girl) 非裔美國男子(左)。非裔美國女孩站在桌子旁(右)。兩張圖片均來自 W.E.B. 杜波依斯彙編和準備的《美國黑人型別》。圖片來源:Getty Images (男子); Getty Images (女孩)

On supporting science journalism 支援科學新聞報道

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by 如果您喜歡這篇文章,請考慮透過以下方式支援我們屢獲殊榮的新聞報道 subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today. 訂閱。透過購買訂閱,您將幫助確保未來能夠繼續講述關於塑造我們當今世界的發現和想法的具有影響力的故事。

But unlike Douglass, DuBois grew leery of photography. Although it was a powerful way to push back against the stereotypes, this tool was starting to work against him. DuBois noticed that “the average white photographer does not know how to deal with colored skins,” he said. And the resulting pictures of Black people were often a “horrible botch.” 但與道格拉斯不同,杜波依斯開始對攝影持懷疑態度。儘管攝影是反擊刻板印象的有力工具,但這種工具開始對他不利。杜波依斯注意到,“普通白人攝影師不知道如何處理有色人種的皮膚,”他說。結果,黑人的照片往往是“糟糕的拙劣之作”。

In 1915, as DuBois struggled with images of Black people, photography—and portrayals of African-Americans in particular—took a hideous turn. That year D. W. Griffithreleased his film The Birth of a Nation. This movie fabricated a false narrative of the Civil War and offered a redemptive account of the acts of the Ku Klux Klan: Griffith depicted the white supremacist secret society saving the nation from lecherous Black people (who were actually white actors in blackface). His film became the most loved movie in the nation. It was even watched in the White House by its fan in chief, President Woodrow Wilson. Griffith was a masterful moviemaker who pioneered the close-up, scenic long shot, and the crosscut. And he created a film that further contaminated the country. Griffith, like DuBois and Douglass, knew the power of pictures. 1915年,當杜波依斯仍在為黑人形象而苦惱時,攝影——尤其是對非裔美國人的描繪——發生了可怕的轉變。那一年,D. W. 格里菲斯發行了他的電影《一個國家的誕生》。這部電影捏造了關於內戰的虛假敘事,並對三K黨(Ku Klux Klan)的行為進行了救贖性的描述:格里菲斯將這個白人至上主義秘密社團描繪成將國家從好色的黑人(實際上是塗黑臉的白人演員)手中拯救出來的英雄。他的電影成為全國最受歡迎的電影。甚至在白宮也得到了其頭號粉絲伍德羅·威爾遜總統的觀看。格里菲斯是一位電影大師,他是特寫鏡頭、風景長鏡頭和交叉剪輯的先驅。他創作了一部進一步汙染了這個國家的電影。格里菲斯和杜波依斯、道格拉斯一樣,深知照片的力量。

Negative portrayals of Black Americans took on a new force as, within a year after The Birth of a Nation, the Great Migration from the South to the North began. While many books will say that African-Americans came to the North for jobs, a truer reason was that they were fleeing for their lives. Terror was the law of the land, and lynchings were very common. For many of these murders, cameras were ringside, capturing burned and broken Black bodies. These photographs were often sold and distributed. Unlike Douglass’s portraits, they were not rendered to make African-Americans more human but less. 在《一個國家的誕生》上映後不到一年,隨著南方到北方的大遷徙開始,對美國黑人的負面描繪獲得了新的力量。雖然許多書會說非裔美國人為了工作來到北方,但更真實的原因是他們為了生存而逃離。恐怖是當時的法律,私刑非常普遍。在許多謀殺案中,相機就在現場,拍攝燒焦和破碎的黑人屍體。這些照片經常被出售和傳播。與道格拉斯的肖像不同,這些照片的目的不是為了讓非裔美國人更像人,而是更不像人。

In this time, the U.S. was a hotbed of intimidation. As the number of lynchings increased, many spoke up against them, but their voices were largely ignored. The Herculean efforts of Black journalist Ida B. Wells, starting in the 1890s, brought these atrocities to the national attention. While Black people knew of them, what the mainstream world needed was proof. And Wells collected statistics of their occurrences and wrote up depictions of lynchings in her newspaper. Beginning in 1916, the NAACP picked up this work. It also found other means to make such murders a part of the public conversation: in the 1920s and 1930s, it flew a flag outside of its building stating, “A Man Was Lynched Yesterday.” Wells and the NAACP used technology to provide hard evidence, and they filled the national consciousness with images and newspaper articles and flagpole alerts in an effort to create change. 在那個時代,美國是恐嚇的溫床。隨著私刑數量的增加,許多人站出來反對,但他們的聲音在很大程度上被忽視了。從1890年代開始,黑人記者艾達·B·威爾斯付出了巨大的努力,將這些暴行帶到了全國的關注之下。雖然黑人瞭解這些暴行,但主流世界需要的是證據。威爾斯收集了這些事件的統計資料,並在她的報紙上撰寫了關於私刑的描述。從1916年開始,全國有色人種協進會(NAACP)接手了這項工作。它還找到了其他方法,使此類謀殺成為公眾對話的一部分:在1920年代和1930年代,它在其大樓外懸掛了一面旗幟,上面寫著“昨天有人被處以私刑”。威爾斯和NAACP利用技術提供確鑿的證據,他們用影像、報紙文章和旗杆警報填滿了國家的意識,以努力促成改變。

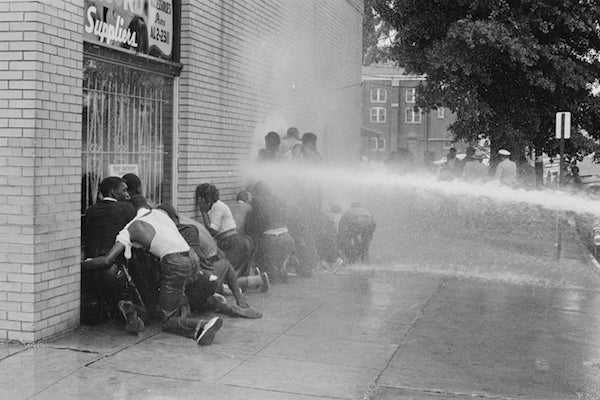

Firefighters use hoses to subdue protestors during the Birmingham Campaign in May 1963. The movement, which called for the integration of African-Americans in schools, was organized by Martin Luther King, Jr., and Fred Shuttlesworth, among others. Credit: Frank Rockstroh Getty Images 1963年5月,在伯明翰運動期間,消防員使用消防水帶來制服抗議者。這場運動呼籲非裔美國人在學校中實現融合,由小馬丁·路德·金和弗雷德·舒特爾斯沃思等人組織。圖片來源:Frank Rockstroh Getty Images

The flash point for that change came from a picture. Lynchings had long been an exertion of power by whites. Then a Black mother named Mamie Till redirected the use of photography as an attack, wielding it against the attackers. She did so by allowing photographs of the open casket of her lynched son, Emmett Till. It was the picture of his mangled and bloated 14–year-old body that catalyzed the civil rights movement. Other pictures, of a Black woman arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a bus in 1955, would be followed, in the 1960s, by film and video footage of young Black protesters hosed by water cannons. The whole world watched as this revolution was born. This younger generation of Black individuals was willing to push back against the oppressive system, unlike the generation before them, because they saw no other way. Years of images of Black people had not changed. They were aware that their own image was beautiful, much as Douglass had hoped, but this was the time to shift how they were viewed in the nation. And it was going to take putting their Black skin in front of harm—and the camera—to do so. 那次變革的爆發點來自一張照片。長期以來,私刑一直是白人行使權力的一種方式。然後,一位名叫瑪米·蒂爾的黑人母親重新定向了攝影的使用,將其作為一種攻擊,用以對抗襲擊者。她透過允許拍攝她被處以私刑的兒子埃米特·蒂爾的敞開棺材的照片來實現這一目標。正是他那14歲、被摧殘和腫脹的身體的照片催化了民權運動。其他照片,例如1955年一位黑人婦女因拒絕在公共汽車上讓座而被捕的照片,隨後在1960年代,又出現了年輕的黑人抗議者被消防水炮噴射的電影和錄影片段。全世界都見證了這場革命的誕生。與他們之前的世代不同,這一代年輕的黑人願意反擊壓迫性的制度,因為他們看不到其他出路。多年來,黑人的形象並沒有改變。他們意識到自己的形象是美麗的,就像道格拉斯所希望的那樣,但現在是時候改變他們在國家眼中的形象了。而要做到這一點,就需要將他們的黑色皮膚置於傷害——以及鏡頭——之前。

Protestors gathered in front of the White House after police-involved shootings of Black people. Credit: Joseph Gruber Alamy 在警察參與槍擊黑人事件後,抗議者聚集在白宮前。圖片來源:Joseph Gruber Alamy

Today pictures from our digital cameras pervade our social media feeds—and our attention. The cameras embedded in our handy cell phones have made it possible for every occasion and amusement to be captured. Yet it was also this technology that helped to spark a racial justice movement. An array of NASA-designed photodetectors, smaller than a thumbnail, sat ready to dispatch an image across the Internet, making it possible for any event to be seen across the globe in real time. It was with a cell phone camera that the video footage of the killing of George Floyd, like a modern-day lynching, became a flash point, much like that of Till a few decades earlier. This time was different, however, because the whole world witnessed it. This time the whole world reacted. This time marchers, both Black and white, cried out that Black Lives Matter. The cell phone camera recorded the misuse of power but also displayed to the protestors that they have their own. 今天,來自我們數碼相機的照片充斥著我們的社交媒體資訊流——以及我們的注意力。嵌入在我們方便的手機中的相機使捕捉每一個場合和娛樂活動成為可能。然而,也正是這項技術幫助引發了一場種族正義運動。一系列美國國家航空航天局(NASA)設計的、比縮圖還小的光電探測器準備就緒,可以透過網際網路傳送影像,從而使全球任何事件都可以即時觀看。正是透過手機攝像頭,喬治·弗洛伊德被殺的影片片段,像現代私刑一樣,成為了一個爆發點,就像幾十年前的蒂爾事件一樣。然而,這一次有所不同,因為全世界都目睹了這一事件。這一次,全世界都做出了反應。這一次,遊行者,無論是黑人還是白人,都高呼“黑人的命也是命”。手機攝像頭記錄了權力的濫用,但也向抗議者展示了他們自身的力量。

For generations, Black Americans have raised their voices about the atrocities against them, using the technology of the time. And one of the ways they displayed racism was by using their Black figure in front of cameras to bring it into better relief. Many allies today have said they were not aware of their privilege or their racism, likening both of them to water for fish. The detection is no longer a mystery, however. Pictures have long provided proof of anti-Black racism, first starting as occasional disturbances in the water in the days of Douglass to the torrent of them flooding our cell phones today. But cameras and their photodetectors can only do so much. They can only bear witness. Once something is seen, the next step is not just to say something but to strategize, to reimagine the future and, most importantly, to act. 幾代人以來,美國黑人一直在利用當時的科技,為他們遭受的暴行發聲。他們展示種族主義的一種方式是將自己的黑人形象置於鏡頭前,以更清晰地展現種族主義。今天,許多盟友表示,他們沒有意識到自己的特權或種族主義,將兩者都比作魚的水。然而,這種覺察不再是一個謎。照片長期以來提供了反黑人種族主義的證據,最初在道格拉斯時代只是水中偶爾的漣漪,到現在變成了今天充斥我們手機的洪流。但是相機及其光電探測器只能做到這麼多。它們只能見證。一旦看到了一些東西,下一步不僅僅是說些什麼,而是要制定戰略,重新構想未來,最重要的是,要行動。